Foram encontradas 100 questões.

FRAYING AT THE EDGES: A LIFE-CHANGING DIAGNOSIS

IT BEGAN WITH what she saw in the bathroom mirror. On a dull morning, Geri Taylor padded into the shiny bathroom of her Manhattan apartment. She casually checked her reflection in the mirror, doing her daily inventory. Immediately, she stiffened with fright.

Huh? What?

She didn‘t recognize herself.

She gazed saucer-eyed at her image, thinking: Oh, is this what I look like? No, that‘s not me. Who‘s that in my mirror?

This was in late 2012. She was 69, in her early months getting familiar with retirement. For some time she had experienced the sensation of clouds coming over her, mantling thought. There had been a few hiccups at her job. She had been a nurse who climbed the rungs to health care executive. Once, she was leading a staff meeting when she had no idea what she was talking about, her mind like a stalled engine that wouldn‘t turn over.

" Fortunately I was the boss and I just said, "Enough of that; Sally, tell me what you‘re up to" she would say of the episode.

Certain mundane tasks stumped her. She told her husband, Jim Taylor, that the blind in the bedroom was broken. He showed her she was pulling the wrong cord. Kept happening. Finally, nothing else working, he scribbled on the adjacent wall which cord was which.

Then there was the day she got off the subway at 14th Street and Seventh Avenue unable to figure out why she was there.

So, yes, she had had inklings that something was going wrong with her mind. She held tight to these thoughts. She even hid her suspicions from Mr. Taylor, who chalked up her thinning memory to the infirmities of age.

"I thought she was getting like me,‖ he said. ―I had been forgetful for 10 years."

But to not recognize her own face! To Ms. Taylor, this was the "drop-dead moment" when she had to accept a terrible truth. She wasn‘t just seeing the twitches of aging but the early fumes of the disease.

She had no further issues with mirrors, but there was no ignoring that something important had happened. She confided her fears to her husband and made an appointment with a neurologist.

"Before then I thought I could fake it,‖ she would explain. ―This convinced me I had to come clean."

In November 2012, she saw the neurologist who was treating her migraines. He listened to her symptoms, took blood, gave her the Mini Mental State Examination, a standard cognitive test made up of a set of unremarkable questions and commands. (For instance, she was asked to count backward from 100 in intervals of seven; she had to say the phrase: ―No ifs, ands or buts‖; she was told to pick up a piece of paper, fold it in half and place it on the floor beside her.)

He told her three common words, said he was going to ask her them in a little bit. He emphasized this by pointing a finger at his head — remember those words. That simple. Yet when he called for them, she knew only one: Beach. In her mind, she would go on to associate it with the doctor, thinking of him as Dr. Beach.

He gave a diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment, a common precursor to Alzheimer‘s disease. The first label put on what she had. Even then, she understood it was the footfall of what would come. Alzheimer‘s had struck her father, a paternal aunt and a cousin. She long suspected it would eventually find her.

Fonte: http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2016/05/01/nyregion/living-with-alzheimers.html action=click&contentCollection=Americas&module= Trending&version=Full®ion= Marginalia&pgtype=article. (acesso em 1/05/2016).

Quanto ao gênero textual, o texto pode ser classificado como

Provas

Questão presente nas seguintes provas

FRAYING AT THE EDGES: A LIFE-CHANGING DIAGNOSIS

IT BEGAN WITH what she saw in the bathroom mirror. On a dull morning, Geri Taylor padded into the shiny bathroom of her Manhattan apartment. She casually checked her reflection in the mirror, doing her daily inventory. Immediately, she stiffened with fright.

Huh? What?

She didn‘t recognize herself.

She gazed saucer-eyed at her image, thinking: Oh, is this what I look like? No, that‘s not me. Who‘s that in my mirror?

This was in late 2012. She was 69, in her early months getting familiar with retirement. For some time she had experienced the sensation of clouds coming over her, mantling thought. There had been a few hiccups at her job. She had been a nurse who climbed the rungs to health care executive. Once, she was leading a staff meeting when she had no idea what she was talking about, her mind like a stalled engine that wouldn‘t turn over.

" Fortunately I was the boss and I just said, "Enough of that; Sally, tell me what you‘re up to" she would say of the episode.

Certain mundane tasks stumped her. She told her husband, Jim Taylor, that the blind in the bedroom was broken. He showed her she was pulling the wrong cord. Kept happening. Finally, nothing else working, he scribbled on the adjacent wall which cord was which.

Then there was the day she got off the subway at 14th Street and Seventh Avenue unable to figure out why she was there.

So, yes, she had had inklings that something was going wrong with her mind. She held tight to these thoughts. She even hid her suspicions from Mr. Taylor, who chalked up her thinning memory to the infirmities of age.

"I thought she was getting like me,‖ he said. ―I had been forgetful for 10 years."

But to not recognize her own face! To Ms. Taylor, this was the "drop-dead moment" when she had to accept a terrible truth. She wasn‘t just seeing the twitches of aging but the early fumes of the disease.

She had no further issues with mirrors, but there was no ignoring that something important had happened. She confided her fears to her husband and made an appointment with a neurologist.

"Before then I thought I could fake it,‖ she would explain. ―This convinced me I had to come clean."

In November 2012, she saw the neurologist who was treating her migraines. He listened to her symptoms, took blood, gave her the Mini Mental State Examination, a standard cognitive test made up of a set of unremarkable questions and commands. (For instance, she was asked to count backward from 100 in intervals of seven; she had to say the phrase: ―No ifs, ands or buts‖; she was told to pick up a piece of paper, fold it in half and place it on the floor beside her.)

He told her three common words, said he was going to ask her them in a little bit. He emphasized this by pointing a finger at his head — remember those words. That simple. Yet when he called for them, she knew only one: Beach. In her mind, she would go on to associate it with the doctor, thinking of him as Dr. Beach.

He gave a diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment, a common precursor to Alzheimer‘s disease. The first label put on what she had. Even then, she understood it was the footfall of what would come. Alzheimer‘s had struck her father, a paternal aunt and a cousin. She long suspected it would eventually find her.

Fonte: http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2016/05/01/nyregion/living-with-alzheimers.html action=click&contentCollection=Americas&module= Trending&version=Full®ion= Marginalia&pgtype=article. (acesso em 1/05/2016).

Quanto à narrativa, o texto é apresentado

Provas

Questão presente nas seguintes provas

FRAYING AT THE EDGES: A LIFE-CHANGING DIAGNOSIS

IT BEGAN WITH what she saw in the bathroom mirror. On a dull morning, Geri Taylor padded into the shiny bathroom of her Manhattan apartment. She casually checked her reflection in the mirror, doing her daily inventory. Immediately, she stiffened with fright.

Huh? What?

She didn‘t recognize herself.

She gazed saucer-eyed at her image, thinking: Oh, is this what I look like? No, that‘s not me. Who‘s that in my mirror?

This was in late 2012. She was 69, in her early months getting familiar with retirement. For some time she had experienced the sensation of clouds coming over her, mantling thought. There had been a few hiccups at her job. She had been a nurse who climbed the rungs to health care executive. Once, she was leading a staff meeting when she had no idea what she was talking about, her mind like a stalled engine that wouldn‘t turn over.

" Fortunately I was the boss and I just said, "Enough of that; Sally, tell me what you‘re up to" she would say of the episode.

Certain mundane tasks stumped her. She told her husband, Jim Taylor, that the blind in the bedroom was broken. He showed her she was pulling the wrong cord. Kept happening. Finally, nothing else working, he scribbled on the adjacent wall which cord was which.

Then there was the day she got off the subway at 14th Street and Seventh Avenue unable to figure out why she was there.

So, yes, she had had inklings that something was going wrong with her mind. She held tight to these thoughts. She even hid her suspicions from Mr. Taylor, who chalked up her thinning memory to the infirmities of age.

"I thought she was getting like me,‖ he said. ―I had been forgetful for 10 years."

But to not recognize her own face! To Ms. Taylor, this was the "drop-dead moment" when she had to accept a terrible truth. She wasn‘t just seeing the twitches of aging but the early fumes of the disease.

She had no further issues with mirrors, but there was no ignoring that something important had happened. She confided her fears to her husband and made an appointment with a neurologist.

"Before then I thought I could fake it,‖ she would explain. ―This convinced me I had to come clean."

In November 2012, she saw the neurologist who was treating her migraines. He listened to her symptoms, took blood, gave her the Mini Mental State Examination, a standard cognitive test made up of a set of unremarkable questions and commands. (For instance, she was asked to count backward from 100 in intervals of seven; she had to say the phrase: ―No ifs, ands or buts‖; she was told to pick up a piece of paper, fold it in half and place it on the floor beside her.)

He told her three common words, said he was going to ask her them in a little bit. He emphasized this by pointing a finger at his head — remember those words. That simple. Yet when he called for them, she knew only one: Beach. In her mind, she would go on to associate it with the doctor, thinking of him as Dr. Beach.

He gave a diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment, a common precursor to Alzheimer‘s disease. The first label put on what she had. Even then, she understood it was the footfall of what would come. Alzheimer‘s had struck her father, a paternal aunt and a cousin. She long suspected it would eventually find her.

Fonte: http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2016/05/01/nyregion/living-with-alzheimers.html action=click&contentCollection=Americas&module= Trending&version=Full®ion= Marginalia&pgtype=article. (acesso em 1/05/2016).

De acordo com o texto,

Provas

Questão presente nas seguintes provas

FRAYING AT THE EDGES: A LIFE-CHANGING DIAGNOSIS

IT BEGAN WITH what she saw in the bathroom mirror. On a dull morning, Geri Taylor padded into the shiny bathroom of her Manhattan apartment. She casually checked her reflection in the mirror, doing her daily inventory. Immediately, she stiffened with fright.

Huh? What?

She didn‘t recognize herself.

She gazed saucer-eyed at her image, thinking: Oh, is this what I look like? No, that‘s not me. Who‘s that in my mirror?

This was in late 2012. She was 69, in her early months getting familiar with retirement. For some time she had experienced the sensation of clouds coming over her, mantling thought. There had been a few hiccups at her job. She had been a nurse who climbed the rungs to health care executive. Once, she was leading a staff meeting when she had no idea what she was talking about, her mind like a stalled engine that wouldn‘t turn over.

" Fortunately I was the boss and I just said, "Enough of that; Sally, tell me what you‘re up to" she would say of the episode.

Certain mundane tasks stumped her. She told her husband, Jim Taylor, that the blind in the bedroom was broken. He showed her she was pulling the wrong cord. Kept happening. Finally, nothing else working, he scribbled on the adjacent wall which cord was which.

Then there was the day she got off the subway at 14th Street and Seventh Avenue unable to figure out why she was there.

So, yes, she had had inklings that something was going wrong with her mind. She held tight to these thoughts. She even hid her suspicions from Mr. Taylor, who chalked up her thinning memory to the infirmities of age.

"I thought she was getting like me,‖ he said. ―I had been forgetful for 10 years."

But to not recognize her own face! To Ms. Taylor, this was the "drop-dead moment" when she had to accept a terrible truth. She wasn‘t just seeing the twitches of aging but the early fumes of the disease.

She had no further issues with mirrors, but there was no ignoring that something important had happened. She confided her fears to her husband and made an appointment with a neurologist.

"Before then I thought I could fake it,‖ she would explain. ―This convinced me I had to come clean."

In November 2012, she saw the neurologist who was treating her migraines. He listened to her symptoms, took blood, gave her the Mini Mental State Examination, a standard cognitive test made up of a set of unremarkable questions and commands. (For instance, she was asked to count backward from 100 in intervals of seven; she had to say the phrase: ―No ifs, ands or buts‖; she was told to pick up a piece of paper, fold it in half and place it on the floor beside her.)

He told her three common words, said he was going to ask her them in a little bit. He emphasized this by pointing a finger at his head — remember those words. That simple. Yet when he called for them, she knew only one: Beach. In her mind, she would go on to associate it with the doctor, thinking of him as Dr. Beach.

He gave a diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment, a common precursor to Alzheimer‘s disease. The first label put on what she had. Even then, she understood it was the footfall of what would come. Alzheimer‘s had struck her father, a paternal aunt and a cousin. She long suspected it would eventually find her.

Fonte: http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2016/05/01/nyregion/living-with-alzheimers.html action=click&contentCollection=Americas&module= Trending&version=Full®ion= Marginalia&pgtype=article. (acesso em 1/05/2016).

Marque a opção correta quanto aos procedimentos solicitados pelo neurologista a Geri Taylor.

Provas

Questão presente nas seguintes provas

FRAYING AT THE EDGES: A LIFE-CHANGING DIAGNOSIS

IT BEGAN WITH what she saw in the bathroom mirror. On a dull morning, Geri Taylor padded into the shiny bathroom of her Manhattan apartment. She casually checked her reflection in the mirror, doing her daily inventory. Immediately, she stiffened with fright.

Huh? What?

She didn‘t recognize herself.

She gazed saucer-eyed at her image, thinking: Oh, is this what I look like? No, that‘s not me. Who‘s that in my mirror?

This was in late 2012. She was 69, in her early months getting familiar with retirement. For some time she had experienced the sensation of clouds coming over her, mantling thought. There had been a few hiccups at her job. She had been a nurse who climbed the rungs to health care executive. Once, she was leading a staff meeting when she had no idea what she was talking about, her mind like a stalled engine that wouldn‘t turn over.

" Fortunately I was the boss and I just said, "Enough of that; Sally, tell me what you‘re up to" she would say of the episode.

Certain mundane tasks stumped her. She told her husband, Jim Taylor, that the blind in the bedroom was broken. He showed her she was pulling the wrong cord. Kept happening. Finally, nothing else working, he scribbled on the adjacent wall which cord was which.

Then there was the day she got off the subway at 14th Street and Seventh Avenue unable to figure out why she was there.

So, yes, she had had inklings that something was going wrong with her mind. She held tight to these thoughts. She even hid her suspicions from Mr. Taylor, who chalked up her thinning memory to the infirmities of age.

"I thought she was getting like me,‖ he said. ―I had been forgetful for 10 years."

But to not recognize her own face! To Ms. Taylor, this was the "drop-dead moment" when she had to accept a terrible truth. She wasn‘t just seeing the twitches of aging but the early fumes of the disease.

She had no further issues with mirrors, but there was no ignoring that something important had happened. She confided her fears to her husband and made an appointment with a neurologist.

"Before then I thought I could fake it,‖ she would explain. ―This convinced me I had to come clean."

In November 2012, she saw the neurologist who was treating her migraines. He listened to her symptoms, took blood, gave her the Mini Mental State Examination, a standard cognitive test made up of a set of unremarkable questions and commands. (For instance, she was asked to count backward from 100 in intervals of seven; she had to say the phrase: ―No ifs, ands or buts‖; she was told to pick up a piece of paper, fold it in half and place it on the floor beside her.)

He told her three common words, said he was going to ask her them in a little bit. He emphasized this by pointing a finger at his head — remember those words. That simple. Yet when he called for them, she knew only one: Beach. In her mind, she would go on to associate it with the doctor, thinking of him as Dr. Beach.

He gave a diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment, a common precursor to Alzheimer‘s disease. The first label put on what she had. Even then, she understood it was the footfall of what would come. Alzheimer‘s had struck her father, a paternal aunt and a cousin. She long suspected it would eventually find her.

Fonte: http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2016/05/01/nyregion/living-with-alzheimers.html action=click&contentCollection=Americas&module= Trending&version=Full®ion= Marginalia&pgtype=article. (acesso em 1/05/2016).

Marque a opção que contém a principal causa da decisão de Geri Taylor em buscar diagnóstico médico.

Provas

Questão presente nas seguintes provas

FRAYING AT THE EDGES: A LIFE-CHANGING DIAGNOSIS

IT BEGAN WITH what she saw in the bathroom mirror. On a dull morning, Geri Taylor padded into the shiny bathroom of her Manhattan apartment. She casually checked her reflection in the mirror, doing her daily inventory. Immediately, she stiffened with fright.

Huh? What?

She didn‘t recognize herself.

She gazed saucer-eyed at her image, thinking: Oh, is this what I look like? No, that‘s not me. Who‘s that in my mirror?

This was in late 2012. She was 69, in her early months getting familiar with retirement. For some time she had experienced the sensation of clouds coming over her, mantling thought. There had been a few hiccups at her job. She had been a nurse who climbed the rungs to health care executive. Once, she was leading a staff meeting when she had no idea what she was talking about, her mind like a stalled engine that wouldn‘t turn over.

" Fortunately I was the boss and I just said, "Enough of that; Sally, tell me what you‘re up to" she would say of the episode.

Certain mundane tasks stumped her. She told her husband, Jim Taylor, that the blind in the bedroom was broken. He showed her she was pulling the wrong cord. Kept happening. Finally, nothing else working, he scribbled on the adjacent wall which cord was which.

Then there was the day she got off the subway at 14th Street and Seventh Avenue unable to figure out why she was there.

So, yes, she had had inklings that something was going wrong with her mind. She held tight to these thoughts. She even hid her suspicions from Mr. Taylor, who chalked up her thinning memory to the infirmities of age.

"I thought she was getting like me,‖ he said. ―I had been forgetful for 10 years."

But to not recognize her own face! To Ms. Taylor, this was the "drop-dead moment" when she had to accept a terrible truth. She wasn‘t just seeing the twitches of aging but the early fumes of the disease.

She had no further issues with mirrors, but there was no ignoring that something important had happened. She confided her fears to her husband and made an appointment with a neurologist.

"Before then I thought I could fake it,‖ she would explain. ―This convinced me I had to come clean."

In November 2012, she saw the neurologist who was treating her migraines. He listened to her symptoms, took blood, gave her the Mini Mental State Examination, a standard cognitive test made up of a set of unremarkable questions and commands. (For instance, she was asked to count backward from 100 in intervals of seven; she had to say the phrase: ―No ifs, ands or buts‖; she was told to pick up a piece of paper, fold it in half and place it on the floor beside her.)

He told her three common words, said he was going to ask her them in a little bit. He emphasized this by pointing a finger at his head — remember those words. That simple. Yet when he called for them, she knew only one: Beach. In her mind, she would go on to associate it with the doctor, thinking of him as Dr. Beach.

He gave a diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment, a common precursor to Alzheimer‘s disease. The first label put on what she had. Even then, she understood it was the footfall of what would come. Alzheimer‘s had struck her father, a paternal aunt and a cousin. She long suspected it would eventually find her.

Fonte: http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2016/05/01/nyregion/living-with-alzheimers.html action=click&contentCollection=Americas&module= Trending&version=Full®ion= Marginalia&pgtype=article. (acesso em 1/05/2016).

Marque a opção em que o item sublinhado NÃO é classificado como um advérbio.

Provas

Questão presente nas seguintes provas

FRAYING AT THE EDGES: A LIFE-CHANGING DIAGNOSIS

IT BEGAN WITH what she saw in the bathroom mirror. On a dull morning, Geri Taylor padded into the shiny bathroom of her Manhattan apartment. She casually checked her reflection in the mirror, doing her daily inventory. Immediately, she stiffened with fright.

Huh? What?

She didn‘t recognize herself.

She gazed saucer-eyed at her image, thinking: Oh, is this what I look like? No, that‘s not me. Who‘s that in my mirror?

This was in late 2012. She was 69, in her early months getting familiar with retirement. For some time she had experienced the sensation of clouds coming over her, mantling thought. There had been a few hiccups at her job. She had been a nurse who climbed the rungs to health care executive. Once, she was leading a staff meeting when she had no idea what she was talking about, her mind like a stalled engine that wouldn‘t turn over.

Fortunately I was the boss and I just said, 'Enough of that; Sally, tell me what you‘re up to' she would say of the episode.

Certain mundane tasks stumped her. She told her husband, Jim Taylor, that the blind in the bedroom was broken. He showed her she was pulling the wrong cord. Kept happening. Finally, nothing else working, he scribbled on the adjacent wall which cord was which.

Then there was the day she got off the subway at 14th Street and Seventh Avenue unable to figure out why she was there.

So, yes, she had had inklings that something was going wrong with her mind. She held tight to these thoughts. She even hid her suspicions from Mr. Taylor, who chalked up her thinning memory to the infirmities of age.

I thought she was getting like me, he said. — I had been forgetful for 10 years.

But to not recognize her own face! To Ms. Taylor, this was the "drop-dead moment" when she had to accept a terrible truth. She wasn‘t just seeing the twitches of aging but the early fumes of the disease.

She had no further issues with mirrors, but there was no ignoring that something important had happened. She confided her fears to her husband and made an appointment with a neurologist.

"Before then I thought I could fake it" she would explain. ― This convinced me I had to come clean.

In November 2012, she saw the neurologist who was treating her migraines. He listened to her symptoms, took blood, gave her the Mini Mental State Examination, a standard cognitive test made up of a set of unremarkable questions and commands. (For instance, she was asked to count backward from 100 in intervals of seven; she had to say the phrase: ―No ifs, ands or buts‖; she was told to pick up a piece of paper, fold it in half and place it on the floor beside her.)

He told her three common words, said he was going to ask her them in a little bit. He emphasized this by pointing a finger at his head — remember those words. That simple. Yet when he called for them, she knew only one: Beach. In her mind, she would go on to associate it with the doctor, thinking of him as Dr. Beach.

He gave a diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment, a common precursor to Alzheimer‘s disease. The first label put on what she had. Even then, she understood it was the footfall of what would come. Alzheimer‘s had struck her father, a paternal aunt and a cousin. She long suspected it would eventually find her.

Fonte: http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2016/05/01/nyregion/living-with-alzheimers.html action=click&contentCollection=Americas&module= Trending&version=Full®ion= Marginalia&pgtype=article. (acesso em 1/05/2016).

Marque a opção em que o item sublinhado é um qualificador.

Provas

Questão presente nas seguintes provas

Texto 1: A mídia realmente tem o poder de manipular as pessoas?

Por Francisco Fernandes Ladeira

À primeira vista, a resposta para a pergunta que intitula este artigo parece simples e óbvia: sim, a mídia é um poderoso instrumento de manipulação. A ideia de que o frágil cidadão comum é impotente frente aos gigantescos e poderosos conglomerados da comunicação é bastante atrativa intelectualmente. Influentes nomes, como Adorno e Horkheimer, os primeiros pensadores a realizar análises mais sistemáticas sobre o tema, concluíram que os meios de comunicação em larga escala moldavam e direcionavam as opiniões de seus receptores. Segundo eles, o rádio torna todos os ouvintes iguais ao sujeitá-los, autoritariamente, aos idênticos programas das várias estações. No livro Televisão e Consciência de Classe, Sarah Chucid Da Viá afirma que o vídeo apresenta um conjunto de imagens trabalhadas, cuja apreensão é momentânea, de forma a persuadir rápida e transitoriamente o grande público. Por sua vez, o psicólogo social Gustav Le Bon considerava que, nas massas, o indivíduo deixava de ser ele próprio para ser um autômato sem vontade e os juízos aceitos pelas multidões seriam sempre impostos e nunca discutidos. Assim, fomentou-se a concepção de que a mídia seria capaz de manipular incondicionalmente uma audiência submissa, passiva e acrítica.

Todavia, como bons cidadãos céticos, devemos duvidar (ou ao menos manter certa ressalva) de proposições imediatistas e aparentemente fáceis. As relações entre mídia e público são demasiadamente complexas, vão muito além de uma simples análise behaviorista de estímulo/resposta. As mensagens transmitidas pelos grandes veículos de comunicação não são recebidas automaticamente e da mesma maneira por todos os indivíduos. Na maioria das vezes, o discurso midiático perde seu significado original na controversa relação emissor/receptor. Cada indivíduo está envolto em uma “bolha ideológica”, apanágio de seu próprio processo de individuação, que condiciona sua maneira de interpretar e agir sobre o mundo. Todos nós, ao entramos em contato com o mundo exterior, construímos representações sobre a realidade. Cada um de nós forma juízos de valor a respeito dos vários âmbitos do real, seus personagens, acontecimentos e fenômenos e, consequentemente, acreditamos que esses juízos correspondem à “verdade”. [...]

[...] A mídia é apenas um, entre vários quadros ou grupos de referência, aos quais um indivíduo recorre como argumento para formular suas opiniões. Nesse sentido, competem com os veículos de comunicação como quadros ou grupos de referência fatores subjetivos/psicológicos (história familiar, trajetória pessoal, predisposição intelectual), o contexto social (renda, sexo, idade, grau de instrução, etnia, religião) e o ambiente informacional (associação comunitária, trabalho, igreja). “Os vários tipos de receptor situam-se numa complexa rede de referências em que a comunicação interpessoal e a midiática se completam e modificam”, afirmou a cientista social Alessandra Aldé em seu livro A construção da política: democracia, cidadania e meios de comunicação de massa. Evidentemente, o peso de cada quadro de referência tende a variar de acordo com a realidade individual. Seguindo essa linha de raciocínio, no original estudo Muito Além do Jardim Botânico, Carlos Eduardo Lins da Silva constatou como telespectadores do Jornal Nacional acionam seus mecanismos de defesa, individuais ou coletivos, para filtrar as informações veiculadas, traduzindo-as segundo seus próprios valores. “A síntese e as conclusões que um telespectador vai realizar depois de assistir a um telejornal não podem ser antecipadas por ninguém; nem por quem produziu o telejornal, nem por quem assistiu ao mesmo tempo que aquele telespectador”, inferiu Carlos Eduardo.

Adaptado de: http://observatoriodaimprensa.com.br/imprensa-em-questao/a-midia-realmente-tem-o-poder-de-manipular-as-pessoas/. (Publicado em 14/04/2015, na edição 846. Acesso em 13/07/2016.)

O autor do texto

Provas

Questão presente nas seguintes provas

Sejam !$ S_1 = \left\{(x,y) ∈ \mathbb{R}^2 : y \ge \mid \left\vert x \right\vert -1 \mid \right\} !$ e !$ S_2 = \left\{(x,y) ∈ \mathbb{R}^2:x^2+(y+1)^2 \le 25 \right\} !$. A área da região !$ S_1 \cap S_2 !$ é

Provas

Questão presente nas seguintes provas

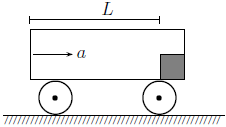

Na figura, o vagão move-se a partir do repouso sob a ação de uma aceleração !$ a !$ constante. Em decorrência, desliza para trás o pequeno bloco apoiado em seu piso de coeficiente de atrito !$ \mu !$. No instante em que o bloco percorrer a distância !$ L !$, a velocidade do bloco, em relação a um referencial externo, será igual a

Provas

Questão presente nas seguintes provas

Cadernos

Caderno Container